The Lummi Nation

"We are the Lhaq’temish. The People of Sea.

We are the original people of Washington’s northern and British Columbia southern coast. For thousands of years, we lived, worked, struggled, and celebrated life on the shores and waters of the Salish Sea. We are fishers, hunters, gatherers, and we live in gratitude of nature’s many gifts. We envision our homeland as a place where we enjoy an abundant, safe, and healthy life; where future generations have the same opportunities to embrace their culture; where all are encouraged to succeed, and none are left behind. We commit ourselves to this vision."

Lhaq’temish Foundation, 2025

This brief history of the Lummi Nation is merely a small portion of what can be said about a people and culture that has existed on Washington’s northern coast and British Columbia southern coast for thousands of years.

“Lummi, the name of a tribe of Indians in Whatcom County, which has been applied to a bay, Indian reservation, Island, point, river and rocks, all in the vicinity of Bellingham Bay.”

Origin of Washington Geographic Names

Edmond S. Meany'

Mary Hillaire was born on February 7, 1927 to Joseph and Edna Hilliare on the Lummi reservation. That same year, Joseph and Frank Hillaire, Mary’s grandfather, testified in The Duwamish, et al, Tribes of Indians vs. United States of America contesting the Point Elliot Treaty. Mary’s father was 32 years old and Frank Hillaire was 82, old enough to remember being a child when the treaty was written and ratified in the 1850s.

Reading the court deposition, it appears that Joseph may have been testifying in place of his father. When he was being sworn in, his occupation was listed as a missionary, though by the time of his passing in 1967, he would be known primarily as a Lummi Indian Chief and carver.

Act 14 of the treaty, authored by Washington Territory Governor Isaac Stevens, reads:

"The United States further agree to establish at the general agency for the district of Puget's Sound, within one year from the ratification hereof, and to support for a period of twenty years, an agricultural and industrial school, to be free to children of the said tribes … and to provide the said school with a suitable instructor… and furnish them with the necessary tools."

The Point Elliot, Medicine Creek and Point No Point treaties in the Puget Sound area ultimately established eighteen reservations. According to Charles E. Mix, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, the purpose behind these treaties was to remove the Indian title to tracts of land "which were needed for the extension of our settlements, and to provide homes for the Indians in other more suitable locations, where they could be controlled and domesticated.'”

Considering the tone of the men who were writing these treaties, it should come as no surprise to the reader that many of the acts agreed upon were violated. The nonobservance extends beyond the essential truth that there was a basic cultural difference between the concept of land ownership between settlers and Native Americans. In the court case that Mary’s father participated in on the year of her birth, the tribes brought forth claims regarding land that was stolen and land that was agreed upon but had never been paid for by the government. The violation of stolen land was more easily quantifiable in court but the government was just as negligent in their violation of the fourteenth Act of the treaty, which promised Indian schools, teachers and supplies free of charge to any tribal leader that put ink to paper.

The first school that was erected on the Lummi reservation was built on marshland at the banks of the Nooksack River. It was reportedly flooded more often than not. There were yearly appeals by the Lummi members to move the school out of the marsh until an industrial log jam by the neighboring Fairhaven Mill Co. took care of the dispute by permanently damaging the school and washing away many of the nearby houses.

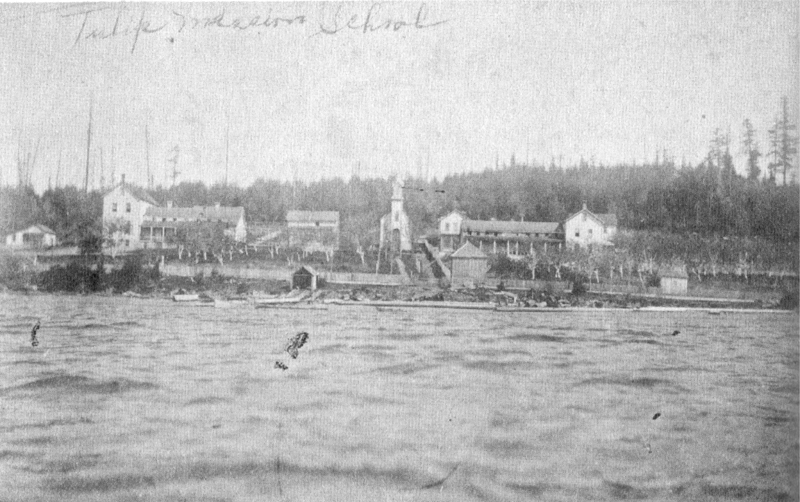

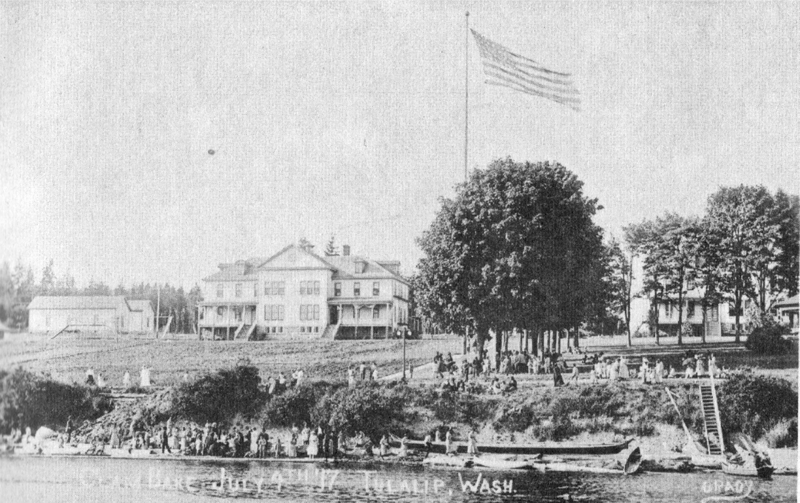

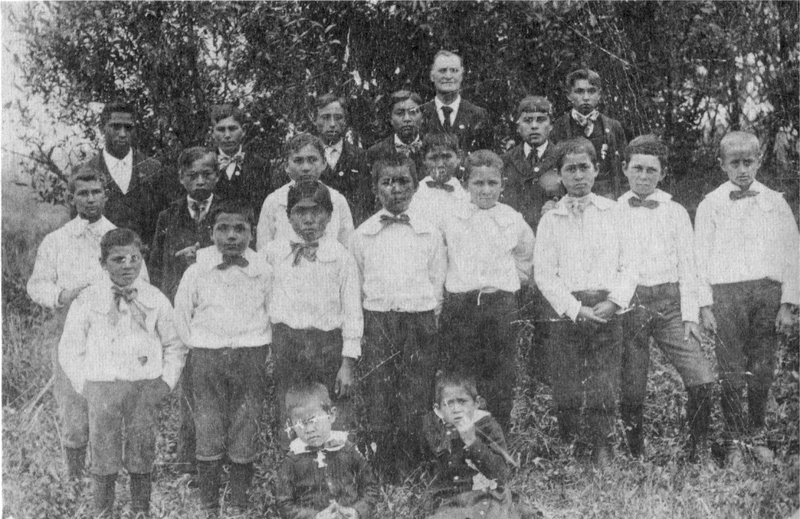

The alternative to this mainly underwater school was the Tulalip Mission, located 70 miles south of the Lummi reservation. The school was first opened by Catholic missionaries in 1857, then slowly incorporated into the Bureau of Indian Affairs after the 1896 abolition of catholic schools on Indian reservations throughout the country.

The Lummi people petitioned the distance of the Tulalip school from their reservation and cited the mortalities of children both on their way to and attending the institution.

The problematic nature of a single school for all Native American tribes of the Puget Sound wasn’t lost on Mary Hillaire when she made this observation on the key role of distance in the failure of the Indian Boarding School system:

“The only reason why it was easy to fail children is that most of the time, the white educators did not have to face Indian parents. Because with the failure of Indian children, the Indian parent’s shame was so great that they very seldom asked why.”

The distance of the children from their parents also allowed for the admission of overt cruelty. Superintendent Charles Buchanan used 50 pound ball and chains on children who attempted to run away. The weights would be dragged by the students for a period of 30 days as an alternative to jail. He was also discovered to club and whip children during medical procedures and as punishment for bedwetting.

After annual petitions from the Lummi people and support from white Education Supervisors W.M. Thornton and William McCluskey, representing the Lummi Nation, Superintendent Charles Buchanan was finally disavowed of his notion “that the Lummi people yet deserve a day school'” by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1908.

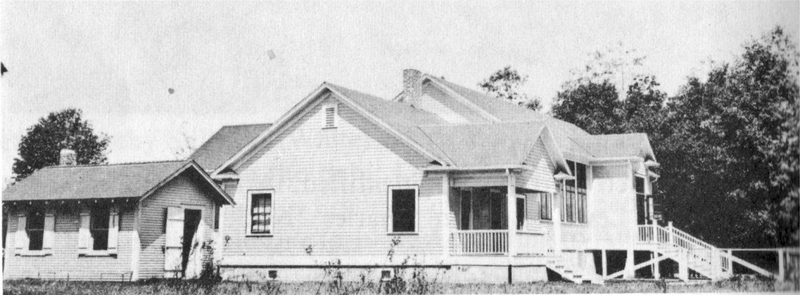

The Lummi Day School was finally constructed on dry ground in 1910, 55 years after it was promised to them in the Treaty of Point Elliot. It was a one room school heated by a wood stove and lit by oil lamps with the capacity for 40 students.

The Day School was later rebuilt and expanded in 1931 where it stands today as the library for the Northwest Indian College, previously the Lummi School of Aquaculture, which Mary Hillaire helped to design.