Overview

“We didn’t have any mission statements back then. The faculty didn’t work with the dean to design their programs. The teachers were responsible for creating their courses, and that’s what Mary did.”

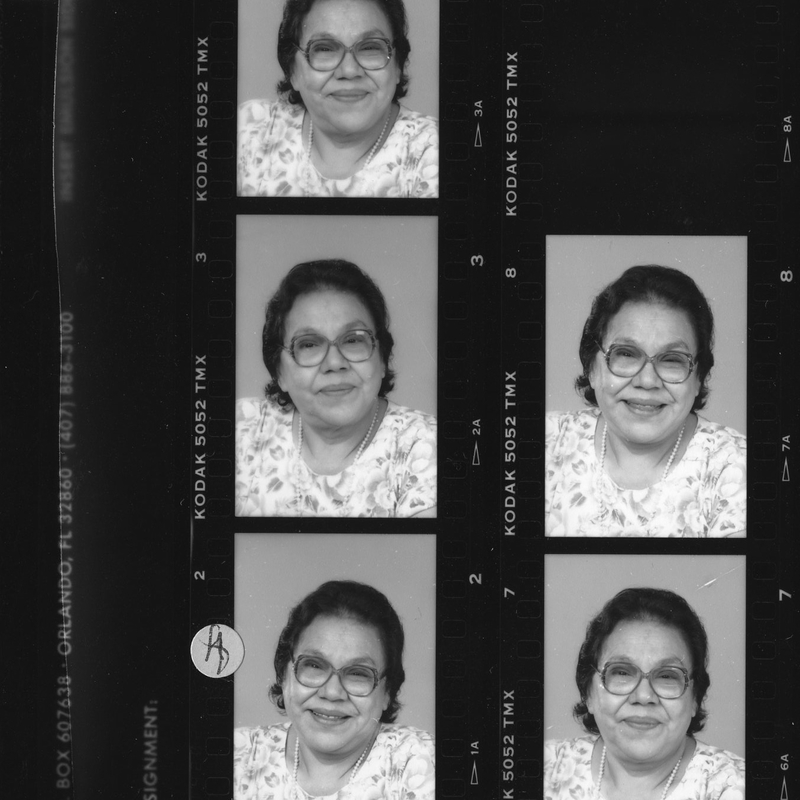

This was relayed matter-of-factly by former Senior Academic Dean and Senior Scholar Barbara Smith during a phone interview I conducted to better understand the Native American Studies program created by Mary Hillaire. I was having difficulty getting a grasp because very little of its history has been put into print, despite the fact that there is a full collection at the Evergreen State College archive dedicated to Hillaire’s work on the program from 1972 up until her passing ten years later.

Faculty members being empowered to create their own program free of the dean’s influence would have been perfectly in line with the progressive values that Evergreen was founded on when it first opened in 1971. Letting a program evolve independently is one thing when it is a class on Ethnopharmacology or the Oral History of the Sierra Nevada Club, as featured on the 1972 course list but a very different thing when it was Mary Hillaire’s vision for the creation of a new higher education system for the Native American people.

As Evergreen literature professor Thad Curtz recalled in 1987:

"She was in the process of exploring, trying to discover ways of doing something that had never been successfully done before, that is, trying to figure what higher education for Native Americans ought to be: how to use useful pieces of traditional Western education and interface with that and how to create an institution within Native American traditions.

Someone told me she once said, “The West has been working on this for two thousand years, ever since Plato. You have to figure it is going to take twenty years, at least, to make it work for the Native American community."

Mary Hillaire joined Evergreen in 1972 as the first female faculty member of the college and implemented the Native American Studies Program one year later. According to a retrospective of the program written by professor Dave Hitchens, the inception for the Native American Studies Program was christened with a signing of a “Native American Manifesto” written by Hillaire which did seem to serve the purpose of a mission statement. He mentions Hillaire’s four principles of the program, “Music, Dance, Talk and Art”.

Mary Hillaire expands on the first principle:

According to Dave Hitchens, the manifesto included the edict that “anything reflective of the Indian culture and/or traditions must be taught by Indian faculty.”

Alongside this principle, in the first years of the program, only Native American students were allowed to enroll.

Mary Hillaire recalled in an audiotape from 1978:

“During the first years of Native American Studies, the program came under a great deal of unfound criticism and misunderstanding by the administration and the faculty of Evergreen. Many of the non-Indian students associating with the students from Native American Studies began to demand entrance into the Native American Studies Program..”

The project was also intended to be at least one third off-campus by way of reservation schools. There were seven locations that went around the coast of the Puget Sound on the S’Klallam, Klallam, Nisqually, Muckleshoot, Quinault, Skokomish and Makah Indian communities. In the tapes from the early seventies, Mary Hillaire seems to have been constantly traveling back and forth between the developing programs on the reservations, giving lectures and recruiting future students.

Map of off-campus reservation schools used for the Native American Studies program since 1973:

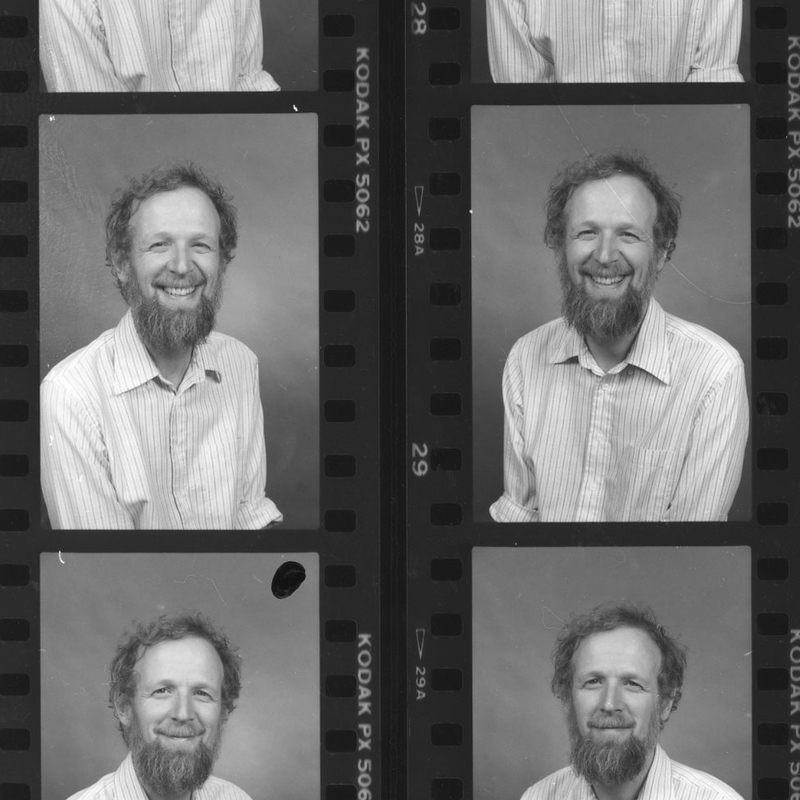

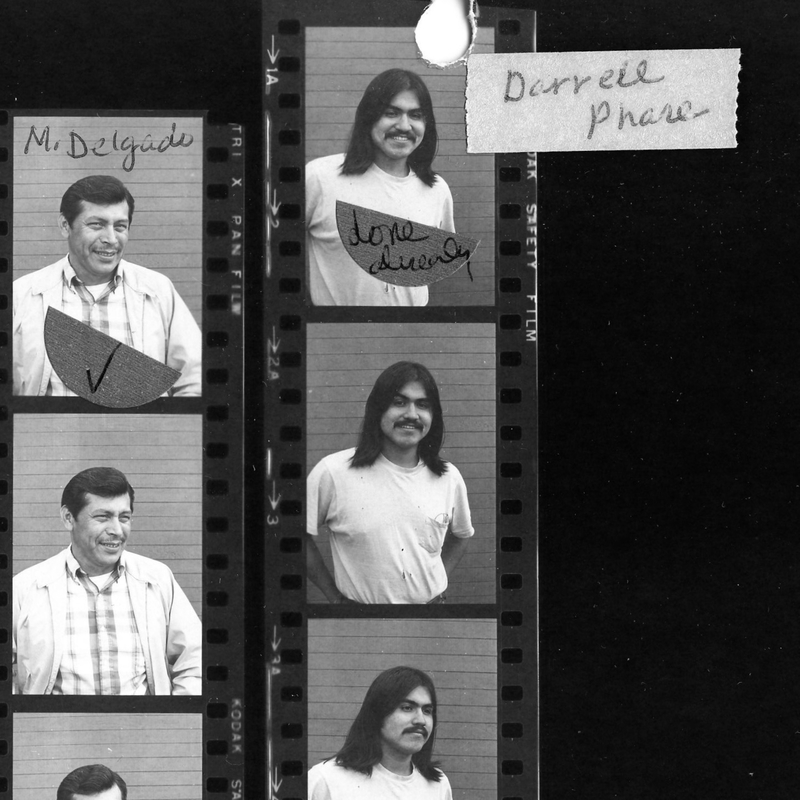

In the first year, Hillaire was given enough funding for four faculty members: Mary Nelson, Cruz Esquivel, Darrell Phare and herself. Esquivel and Nelson were from the Colville tribe and Phare shared Hillaire’s Lummi background.

In my research, I have not been able to find any firm data on what the first year of the course consisted of, although it was likely dictated by Hillaire’s fundamentals of “music, dance, talk and art” rather than western pedagogical standards of reading and writing.

Some insight into the first years of the program is revealed through an interview with Hillaire in the Evergreen student newspaper, The Cooper Point Journal, published in November 18th, 1973:

"The purpose of the program is to establish an educational service relevant to the needs of Indian people. The self determination of Native Americans in their own education is essential. It is time for Indians to have an effect on their education rather than the education having an effect on Indians.”

Rather than focusing on post-high school graduates, Hillaire’s program was primarily designed towards working adults. Hillaire developed a structure for the program where adults could apply their previous life experience to equivalency in academic credit. Hillaire described it this way in a recruiting meeting in 1973.

"If these people come, if some of the older people who have the strength come and say, “I have had this many years working in baskets” and the instructors help those people write this out in what the whites call “Educational Terms”. They have learned both the techniques and the procedures, so we can say that this person has the equivalent of a graduate course."

One difficult area to get accurate information is around enrollment during the first years of the program, likely due to reservation students being included in some reports but not in others. According to some accounts, the first year of the program appears to have been met with great response, with 75 students enrolled and 25 on the waiting list, and the program only waned in student interest by the mid eighties. According to other accounts, there were only two on-campus students the first year of the program and the course had been dropped in 1975 due to low enrollment. According to the Cooper Point Journal:

"There will be no Native American Studies program this year. Academic Dean Lynn Patterson explained that the two-year-old program had not been proposed by any faculty member last fall and that the deans weren’t aware of student interest… Only 39 out of last year’s 98 Native American students have registered for next year."

The speech by Dave Hitchens mentioned earlier cites this decline in the mid-seventies to the change in policy to admit non-Native American students in order to keep the program afloat: “The model had built into it the flexibility to evolve as it has- namely, absorption of larger numbers of Non-Native American Students when Native American enrollment declined.”

In an interview from 1976, Mary Hillaire contradicts this account of why the program was opened up to non-Indian students:

"For 1973-74, we had all Indians. And then as their first step to try and dismember that problem, they asked Cruz Esquivel, who is really, up until 1973-74, he called himself a Mexican.

So they asked him if he would take the program and open it to whites. And so, 1974-75, there was 75 whites learning how to make teepees, so I re-emphasized that I was not developing a program for somebody to study Indians. I was developing a program for Indians to study."

Throughout the seventies and early eighties, Mary Hillaire reported difficulty obtaining funding for the program. Cruz Esquivel discussed creative inventory maneuvers for the distribution of books and supplies between reservation schools that fluctuated year over year depending on enrollment.

Hillaire revealed that the program was being aided by the Presbyterian Church due to the lack of academic support and that she was accused of inappropriately handling funds by Vice President and Provost Ed Kormandy in the late 1970s.

The archive that I have culled most of this exhibit from is known as the Mary Ellen Hillaire Papers, 1950-1983, though printed material makes up the smallest segment of the archive. The majority of the collection is audiovisual. Out of 2142 audiocassettes, 44 audiotapes, 64 videos and 1518 slides, there is only one small box of text documents in the entire collection.

As a faculty member, Hillaire would send out her quarterly reports in long, dictaphone recordings sent to the Dean’s office, rather than inside written reports. The recordings range from 45 minutes to two hours in length and would vary from dry, budgetary lists to emotive departures about the importance of the program to the future of the Native American people.

In addition to recording meetings, lectures and notes, Hillaire also recorded the majority of her phone conversations that she took in her office on campus. As a researcher, I am not sure if the other people in the phone conversations were aware that they were being recorded or if it was common knowledge that this was one of her habits.

I am also unsure what the incentive was behind this practice, but it feels very reminiscent of the Watergate scandal that was culturally dominant while the program was going through its formative years.

Throughout quarterly reports, reservation lectures and program meetings (Mary refused to attend Evergreen faculty meetings), Mary Nelson and Darrell Phare are either silent or absent during the meetings. The only vocal member of the founding faculty is Cruz Esquivel, a music and philosophy professor with Jesuit training, who begins to balance Mary’s intoned speeches with his measured, trenchant contributions to the meetings.

In this excerpt, Esquivel explains the program’s goals for giving students the ability to navigate both white and Native American values.

The content of what I found in the audio tapes is complicated. In the first year of the program, faculty members were published accusing the Dean and college faculty of being “racist bigots.” This accusation was consistent throughout my research from 1970 to 1988.

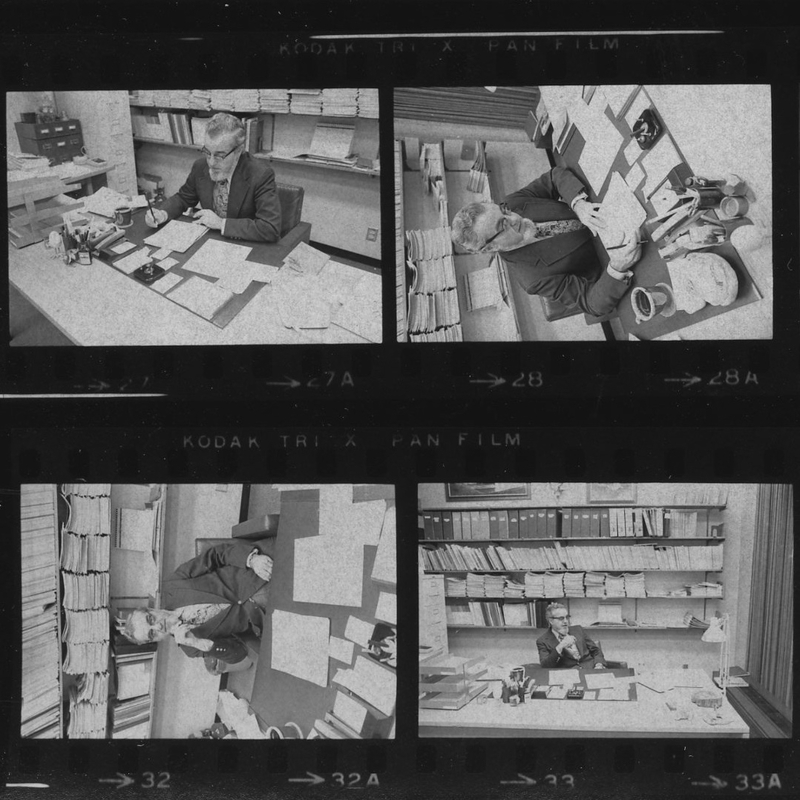

When there were white speakers attending the meetings such as librarian and archivist Malcolm Stilson, he was introduced as “one of the good ones.” Cruz Esquivel relates a similar story in 1973 about being referred to by a white faculty member as if he were not Native American. Hillaire recalls multiple occasions where this happened to her as well.

In the midst of this complicated environment that we hear on the tapes, there also emerges a force of character in Hillaire that gives the listener a remote sense of the strength that enabled Hillaire to manifest her vision of a system of higher education for Native American people.

This vision was, at various times, at odds with the student body, the college administration, state agencies and, in her opinion, her own Lummi values. Creating the program also required her to act in defiance of nearly a century of substandard educational practices implemented on the indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest.