"My Dad, in his generation… worked with the state department, striving to bring in to the more creative and a more useful way, the talent that we have for fishing. And it didn’t work. In the later years in my father’s life we talked much about this idea of the Lummi’s resource, of the condition of poverty among Indians in this area… and we approached many times the idea of a marriage between the native abilities for fishing and the technological skill of production."

The Treaty of Point Elliot, article five states, “The right of taking fish at usual and accustomed grounds and stations is further secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the Territory.” Even with this article protecting this natural resource, Commissioner Charles E. Mix’s underlying objective was to concentrate the Native American people and get them reliant on farming rather than hunting and gathering. To aid in this cultural shift after the signing of the treaty, the U.S. government sent out a “Farmer-in-charge” to each of the reservations to teach agriculture and urge them to grow plants rather than forage them and raise livestock rather than leave the reservations in their fishing boats. In the case of the farmer-in-charge appointed to the Lummi reservation, he had a particularly difficult time arguing his case. In the words of Vine Deloria Jr in his Indians of the Pacific Northwest,

"The reservation was covered with a thick growth of cedar, and when the agent surveyed it into allotments and began his farming program, problems began to pile up rapidly. The men were recruited to cut and burn the trees… so that the land would be clear for farming. But since the land was really an island, clearing the trees resulted in the creation of many swamps and pools of almost perpetual duration."

With the land largely nonarable and the proximity to fishing so near, many Lummi people only took up agriculture during the off-season, if at all. In 1891, A farmer-in-charge wrote:

“One of the largest and naturally most fertile of the five reservations is the Lummi, but, being more remote and less accessible from the agency than are the others, the same discipline cannot easily be maintained with these Indians.... They are more independent and show less inclination to cultivate their land than do the Indians of most of the reserve.”

This inclination to maintain their traditional fishing methods was eventually threatened by the Alaska Packers Association. The company had been slowly encroaching on the shoreline since the early 1890s, obstructing Lummi people from fishing their shores on the Puget Sound and driving them from their camps. Letters to the Bureau of Indian Affairs went unanswered, so Lummi elders took the Alaska Packers Association to Washington State court in 1897 and to the Supreme Court in 1899, both of which were dismissed in favor of the association, resulting in the forced ejection of the Lummi Tribe along the Point Roberts and Lummi Island coast. Though the Lummi people began contesting the treaty violation as early as 1913, much of the progress was made just before or during the creation of Mary Hillaire’s Native American Studies program.

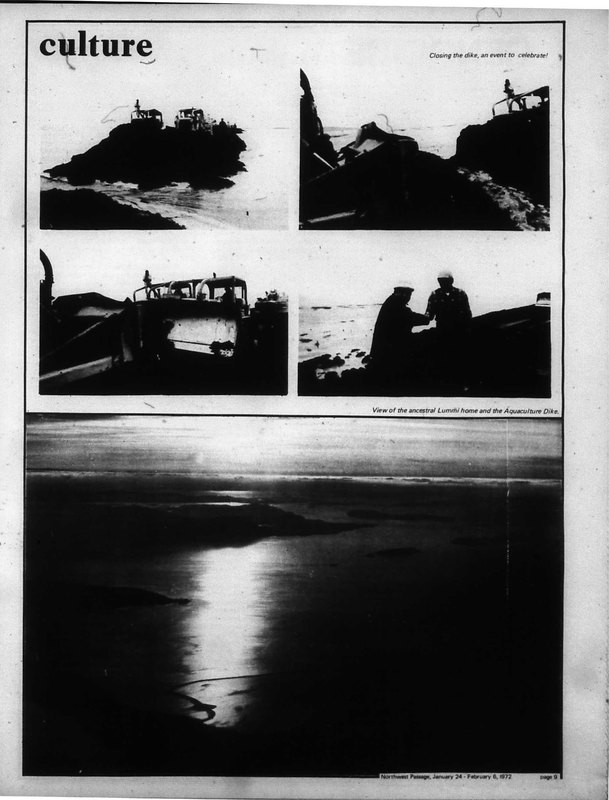

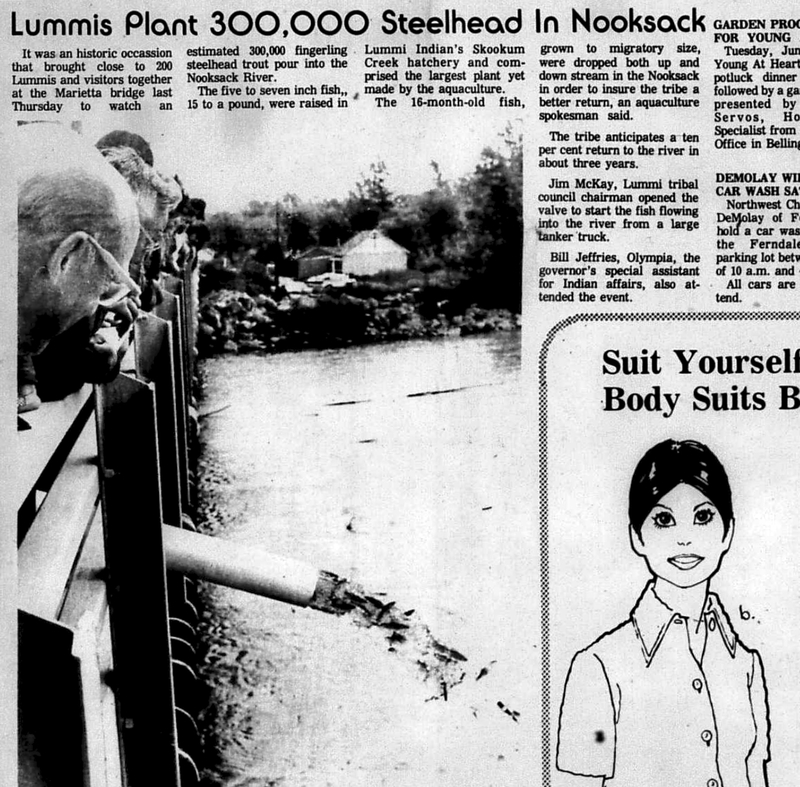

In 1968, the State Oceanographic Commission gave the Lummi people a grant of one thousand dollars to survey Lummi Bay as a potential site for aquaculture, or the rearing of aquatic animals or plants for food. The survey concluded that “the tidelands could be converted into a large pool with just the right depth to allow a number of fish to grow.”

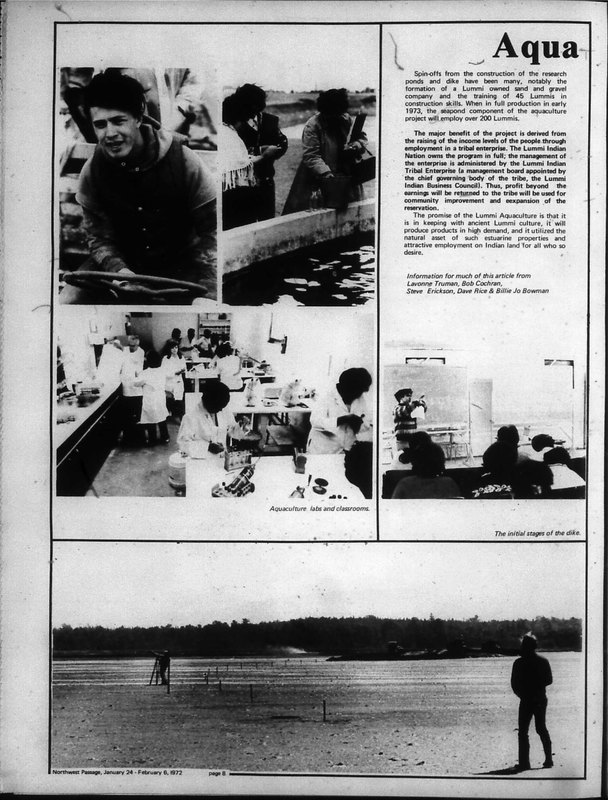

Once the Lummi Nation came forward with their plans, they were immediately met with a backlash from both the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Lummi Bay Beach Association, who owned most of the property along the bay. The association attacked the Lummi aquaculture program as “a waste of money and a dangerous precedent in allowing uneducated Indians to run things.” Insults and accusations like these directly influenced the creation of the Lummi School of Aquaculture, so that they could educate themselves independently instead of relying on licensing from the US Army Corps of Engineering as they needed to do during the initial stages in the early seventies.

Mary Hillaire cites on many different lectures her participation in the creation of the Lummi School of Aquaculture, though I have been unable to find any supporting material around this claim. What can be ascertained from Hillaire’s records is that she graduated from Western Washington State College in 1956 and completed a Masters in Education 10 years later, a year before she talks about contributing to the design of the Lummi School of Aquaculture.

Following the completion of Hillaire’s education, she spoke about being hired by the Department of Education in Washington D.C. to evaluate Native American programs across the country. Hillaire talked about being offered a job in London and the difficulty of staying in touch with Native American people. She discussed how she came up with the idea for Native American Studies after seeing the inadequacies of the pre-existing programs and returning to Washington state to put them into motion. During Hillaire’s first year with the college in 1972, she taught a course called Contemporary Minority Program and gave a lecture at the American Association for the Advancement of Science called, “Relating Science to a Cultural Life-Style: Teaching Aquaculture among the Lummi.”

In 1973, when the program officially launched at Evergreen, Hillaire visited many of the surrounding reservations to explain her vision to tribal leaders. These recordings contain many of the most honest insights into Hillaire’s personal history. They include accounts of being “thrown out” of third grade when she was a child and “having the inability to read” when she returned. There is also the disclosure of what may now be interpreted as dyslexia.

"I was thrown out of school when I was in the third grade. They just let me go to school but fail and fail and fail all the time. When I went back to school, I didn’t know how to read. So, two years, I had to learn a different way to get my grades. I couldn’t read.

And I couldn’t today read.

I understand material because I understand what people are doing. And if they could tell me the year that this was written, I could tell them what it’s written about. And teachers have told me “I’ve never knew anybody that was so insightful, and I hadn’t even read the book. But I know people."

Mary also recalled that her bosses insisted she contribute to office meetings. She told the small group she was lecturing to that once she got over her insecurities, she found herself unable to stop. In Dave Hitchen’s history of the program, he cites a student from 1973 recalling, “I was not used to elders talking at such length. Mary Hillaire would talk for eight hours without stopping.”

The volume of the tapes in the Mary Ellen Hillaire Papers cover nearly every facet of Hillaire’s life between the years of 1972 to 1982. We hear Mary Hillaire lecture nonstop during an eight hour class, lead a faculty meeting where she held the floor save for two or three interjections, give a recruitment lecture at a reservation two hours away and then go home to dictate reports.

As with many prolific figures, when listening to the tapes, it is impossible to avoid speculating whether Mary may have somehow been both extremely involved with her community in one sense and profoundly isolated in another. Mary Hillaire was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1980 and continued to work with the program until her passing in October 2, 1982.

One of my areas of interest in Mary Hillaire’s story is between the period of 1970 to 1971, when she chose to implement her Native American Studies program at The Evergreen State College. Considering that the program’s founder and staff accused the administration of racism within the first year of implementation, openly joked that none of her staff wanted to be on campus and stated, “unless they fire me, I will never work with whites.” Evergreen seems like an odd choice.

Was it a matter of funding that was unavailable from the tribal universities, the first of which had only opened three years earlier? Was it the perceived leniency of a more liberal college that would allow the program to develop according to Hillaire’s vision? Was it that Hillaire wanted a platform where she could reach out to many tribes instead of just the Lummi people? By the time of her passing, she was working with twelve Native American tribes in Washington and receiving Native American students from the Southwest and Northeast United States.

A partial answer may be found in this recording from 1973 when an unidentified speaker asks Mary, “Now, is this something that you want to do as a part of Evergreen? How are you going to fit this into it?”

"I kinda had a hang-up here. I figured that we paid for this. That we paid for a place in whatever system is workable for us and that the higher education system, while not totally beneficial for anyone, can be more beneficial if we take part."

Professor Dave Hitchens described the relationship of the Native American Studies program to The Evergreen State College as an “experiment within an experiment” that the school had simply, “lost sight of.”

While Mary’s battles with school administration are in bold print throughout the Mary Ellen Hillaire Papers archive, there is also a current of contention between Mary and the Lummi community. Though there are no specific details of what happened, there are a few rare moments when Mary discussed her relationship to the Lummi Nation in the wake of her academic achievements.

"I have been suspected by my Indian family and friends that I succeeded academically and failed as a Lummi. I do not feel that education should do this, that it should open the opportunity on the one hand while denying the ultimate on the other. The ultimate is, that the best day and the worst day of my life, I will be Lummi."

Mary’s sister Pauline Hillaire wrote, “Rights Remembered: A Salish Grandmother Speaks on American Indian History and the Future”, in 2016, recalling Lummi history, politics and fishing rights in 2016, but there was surprisingly little about Mary excluding this brief, aside:

"The foundation for Mary Ellen's Native American Studies Program was our Coast Salish Value system. The system has nothing to do with money, power, sex or any form of egotism...

It was a struggle to get the college to understand and accept, but they did."

In an undated tape marked simply “01 - Native American Studies”, Mary Hillaire said this about the importance of taking part:

"There are some things that we have to take as human beings on faith. The network- my Dad used to call it the, “person to person human bridge to understanding.” We don’t all have to be at this point or that point or the farthest point. All we have to be is in the system that works together.”