Contracted Studies and Coordinated Studies: Academic Planning Conference, February 8 & 9, 1970

Excerpt from the minutes of the first meeting of the Board of Trustees, Governor Daniel J. Evans presiding, August 30, 1967:

Senator Gordon Sandison, co-sponsor of the founding legislation, “said that it was not the intent of the Legislature that this be just another four-year college, that it was an unique opportunity to meet the needs of the students of today and the future because the planning would not be bound by any rigid structure of tradition as are the existing colleges nor by any over-all central authority as is the case in many states.

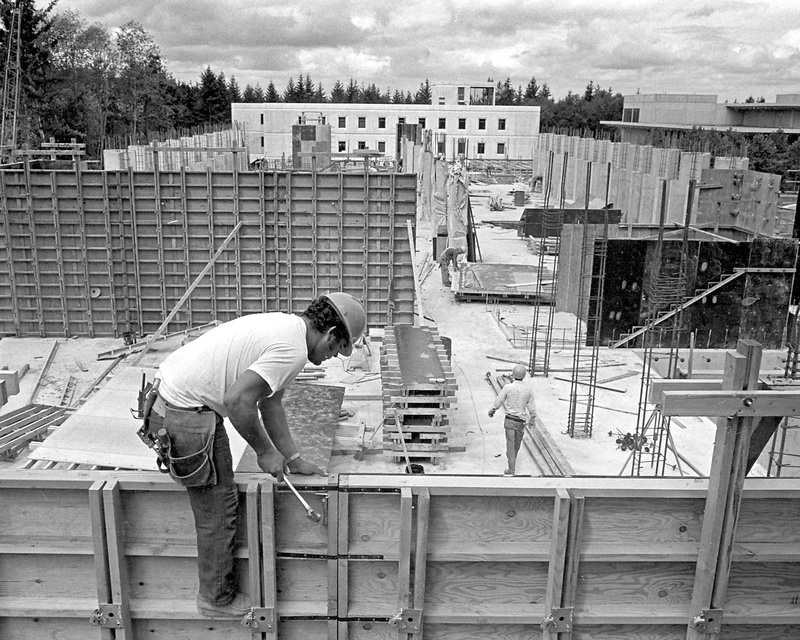

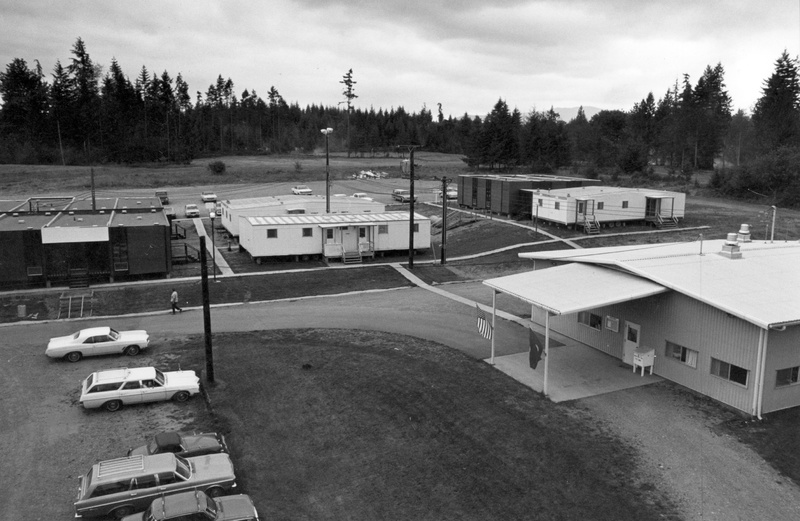

The offices of the College began in a senate committee room in the legislative buildings, where Executive Assistant to the Trustees Dean Clabaugh and a small staff conducted the presidential search. From there, offices moved to a former Plywood Workers Credit Union building, and from there to campus. Modular office spaces opened on campus in October 1969, to augment existing buildings (the Probst house and meatpacking plant, later demolished).

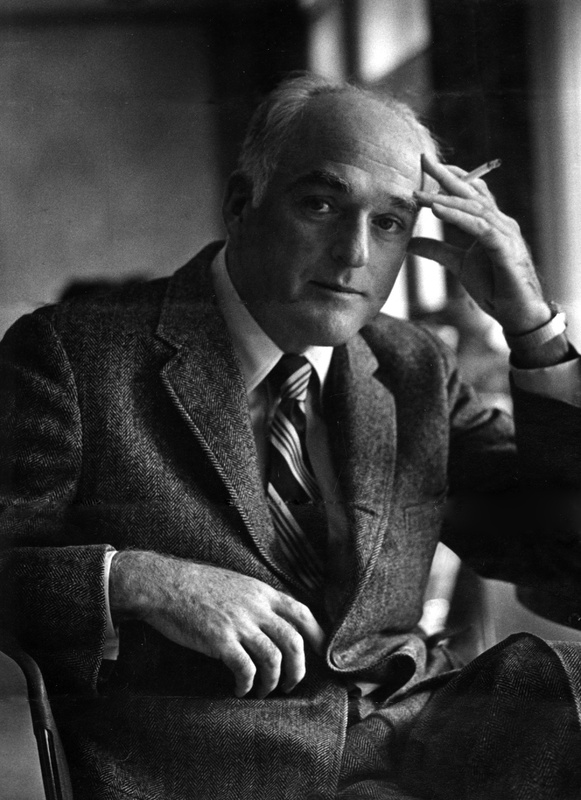

The broad vision and goals for Evergreen were established from 1967-1969 by Governor Daniel J. Evans, the early Trustees, President McCann, the first three Vice Presidents (Dean Clabaugh, E. Joseph Shoben , and Dave Barry), a blue-ribbon panel of experts, and consultants from Arthur D. Little & Co. In broad terms, their vision was to create a college that would attract students who wouldn’t or couldn’t attend traditional universities, to serve southwest Washington and state government, and to create an environment in which students would quickly become independent and direct their own education.

Many of the assumptions and aspirations of this group were influenced by a commitment to liberal education as a route to personal freedom in a democratic society, and they had an appetite for educational reform. As McCann recalled in 1987, at his job interview with the Trustees:

“I told them I did not want departments, I didn't think grades made any sense, I didn't think tenure as such made any sense. . . I thought students ought to get job experience for credit, that they ought to have plenty of opportunity for individual study, and that faculty ought to work together. All of that in terms just that vague. I didn't have the slightest idea how it would be put together into an operating college.”

The Evergreen State College Review, February, 1987; Volume 8, Number 2

Reform efforts at existing universities had been stymied by vested interests and departmental turf battles, and the visionaries saw in Evergreen an opportunity to start from scratch, and to design a “free university” that would appeal to a generation demanding civil rights, equal rights, and decolonization. McCann expressed confidence that a general education, rather than specific career preparation, would best serve students.

In McCann’s words, at Evergreen:

“Students will work as colleagues with faculty and others, and together these people will try (that word is emphasized because it involves all of the college’s people in continual change) to create a place whose graduates can as adults be undogmatic citizens and uncomplacently confident individuals in a changing world.”

“Vital Undergraduate Studies: What’s the Right Climate?”

August 28, 1969

McCann imagined a college in which students would attend four contiguous years, the final two of which would be comprised of independent study and internships. He viewed courses with suspicion as well as their associated credit system, which he found too often measured time spent in seats rather than accomplishments or authentic learning. To place flesh on the bones of this vision in 1969 he hired Provost David Barry who in turn in early 1970 hired the first three Academic Deans: Mervyn Cadwallader (Dean of Social Sciences), Donald Humphrey (Dean of Natural Sciences and Mathematics), and Charles Teske (Dean of Humanities and Arts). It is this group that cemented interdisciplinary study as a fundamental aspiration for Evergreen. They changed their titles to the generic “Academic Dean” and adapted from the State Department the concept of “desk assignments” to distinguish their administrative tasks. The first opportunity for the three Deans to meet each other arrived in early February, 1970.

On February 8 and 9, 1970 Provost Dave Barry presided over the Academic Planning Conference, and through the course of two days the Deans led the group to the conclusion that “the faculty would be assigned by the Provost and Council of Deans to plan for and to serve in interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary project groups or task forces,” elsewhere called “theme groups.” These eventually came to be called “coordinated studies programs,” to be supplemented with “contracted studies” for advanced projects or independent research.

Merv Cadwallader brought to the table substantial experience with what we would today call a learning community in coordinated studies. He had led two iterations, in 1965-1967 and 1967-1969, of a full-time general education program contemporaneous with Joseph Tussman’s “Experiment at Berkeley,” both built upon the “great books” full-time immersive general education Alexander Meiklejohn created at the University of Wisconsin from 1927-1931. Crucial elements Cadwallader found necessary for success at San Jose State included deep collaboration among faculty teams, clarity among students and faculty that they were exploring a central theme or problem, and authentic community relationships. He recalled in a paper delivered in 1981:

“We opened each semester with a retreat to the mountains to talk about the theme of the program, and we rounded off the program with a final retreat. We stressed communal activities within the program, sent the students out in teams to study small agricultural communities, and got students involved in planning our fourth semester. Finally, we encouraged informal writing and eliminated conventional grading.”

1981

Cadwallader accepted the appointment at Evergreen hoping that perhaps one hundred students and five faculty could engage in coordinated studies. At the February 8, 1970 Academic Planning Conference he described his San Jose State experience. Charlie Teske replied with enthusiasm for making that model the core of Evergreen’s first year, in part because the approach would solve a vexing problem: which faculty to hire for the planning year (1970-1971). By establishing the “theme groups” first, the Deans could then recruit faculty capable of guiding students through those themes and, Teske believed, the appropriate distribution of faculty disciplinary expertise would fall into place. Representing the sciences, Don Humphrey concurred, asking “Well, if it’s good for 100 people, why isn’t it good for 1,000?”

Together with the Academic Deans, the Planning Year Faculty (1970-1971) created the first Coordinated Studies Programs.

Audio of the February 8 & 9 Academic Planning Conference

Merv Cadwallader’s description of his San Jose State experience begins at one hour and fifty-five minutes into the first recording; discussion of what this model would mean at Evergreen follows.

Provost Dave Barry saw promise in the proposal put forward by the Deans: at least for the first two years of operations, when most of the students would be in their first and second years of study, “interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary project groups or task forces” would create the core curriculum, to be filled out with “contracted studies” in specialized inquiry or individual or group projects.

Executive Vice President Joseph Shoben saw merit in the proposal, but also raised concerns. In September 1970 he wrote to Cadwallader:

“… the program as you outlined it is indeed a Tussman derivative – if not pure and undefiled, then modified by only some interesting but minor impurities and defilements. It is worth noting that the dropout rate in Tussman’s own program at Berkeley runs about 55% from a highly self-selected population…. As deeply attractive as this option is, it is very probable that it is suitable for only a fraction – perhaps a large one but still a fraction – of the undergraduates whom we must serve. Does our proposed arrangement give us the scope and diversity necessary to permit our accomplishing out mission? Does it define the only way in which we are going to help students learn how to learn?”

Memo from Shoben to Cadwallader

Shoben advocated strongly for contracted studies, and for the principle that staff as well as faculty could create contracts with students, and mentor students through learning activities tailored to their needs . As Executive Vice President for Administration, Shoben’s portfolio included the Library, Student Affairs, and Communications, all of which he proposed as arenas of student learning for credit.

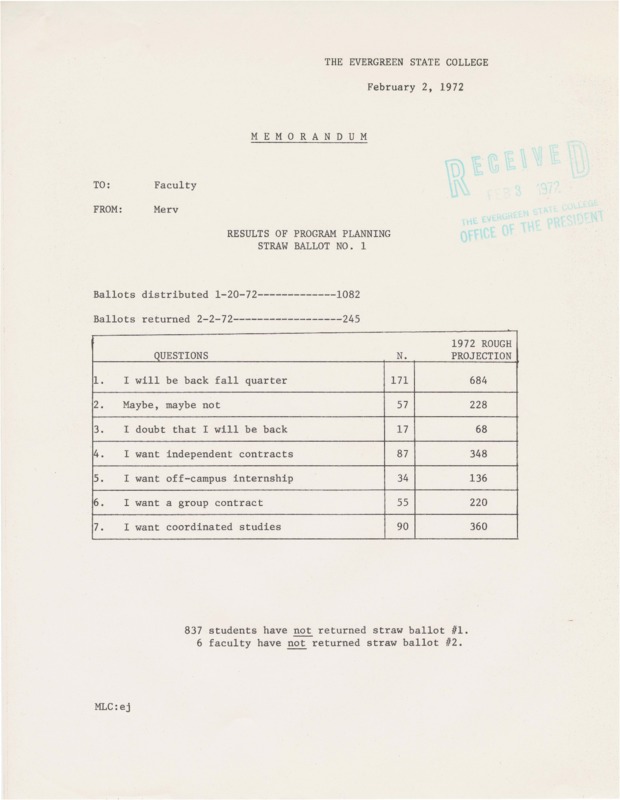

Shoben’s insight proved to be prescient. During January 1972, the winter quarter of the first year, Cadwallader surveyed students to gain an understanding of what kind of curriculum to prepare for the second year. Of students responding to the survey, 30% indicated they were unlikely to continue at Evergreen. Of those who contemplated returning, roughly 40% wished to continue in coordinated studies whereas 60% preferred an off-campus internship or contracted study. These latter modes of study resonated with students who were attracted to Evergreen by the promise of freedom of choice and self-designed study.

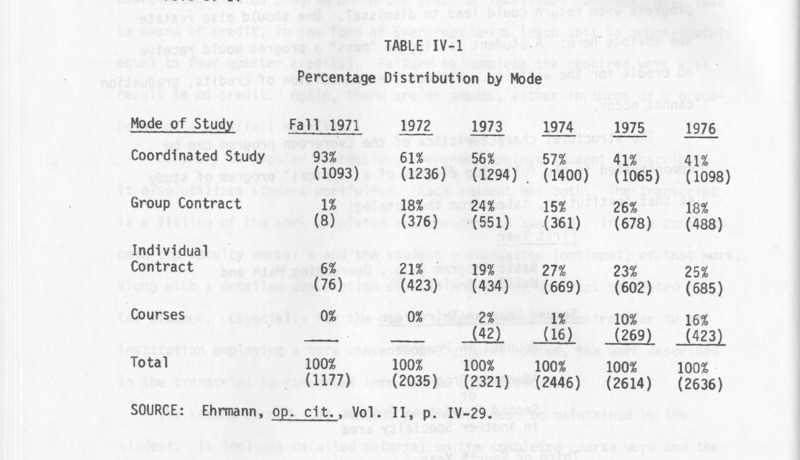

From 1971 to 1976 the percentage of students registered in coordinated studies fell from 93% to 41%. Group contracts typically matched one faculty member to twenty students pursuing advanced work on a common theme. These increased from 1% to 18%. Student-originated independent contracts increased from 6% to 25%. Courses also increased, from 0% to 16%.

By the end of the 1970s, Evergreen alumni demonstrated that the College prepared them exceptionally well for success in their chosen careers. Nonetheless, critics were dubious, especially about contracted studies. Credible stories circulated about insufficiently supervised independent study.

During the 1970s the public higher education system in Washington State had built more undergraduate capacity than was needed, and late in the decade enrollments at Evergreen began to decline. The Legislature commissioned the Council on Postsecondary Education (CPE) to conduct a study and offer recommendations, including traditional modes of learning. However, the study confirmed Evergreen’s academic success, argued against fundamental change, and recommended adjustments and adding graduate programs.

Those adjustments included increasing the quality of individual study via contracts, in part by limiting their number.

The late 1970s were a high-water mark for contracted studies, and a low-water mark for coordinated studies. As access to independent study gradually contracted during the 1980s and 1990s, coordinated studies solidified its place as the hallmark of an Evergreen education.